August 29, 2018

The conditional marker mohon

The conditional mohon serves as a marker indicating that the proposed condition is more favorable than the current one.

Example 1:

Juan: Un chuli’i yo’ Pepsi? Coke mohon.

You got me a Pepsi? It should’ve been Coke.

Example 2:

Maria: Mana’i si Tito ni scholarship. Guahu mohon.

Tito was given the scholarship. It should’ve been me.

Mohon is also used to indicate hypothetical situations or situations that are now too late for their condition and their result to exist.

Examples:

Chumochochu yo’ mohon yanggen mamahan hao nengkanno’.

I’d be eating if you had bought food.

Mafatto yo’ mohon Guam yanggen ti pumakyu.

I’d be arriving in Guam, if it didn’t storm.

Humugando yo’ mohon, lao gof malangu yo’.

I would’ve played, but I’m very sick.

Masisinek yo’ mohon yanggen guaha påpet kommon.

I would be taking a dump right now if there was toilet paper.

With yanggen

Because it is a conditional marker mohon is often used in conjunction with yanggen in the expression yanggen mohon.

Examples:

Yanggen mohon humanao hao para i tenda, esta mama’titinas yo’ titiyas.

If you had gone to the store, I would be making titiyas right now.

Yanggen mohon hu tungo’ na gaige hao gi espitat, bai hu bisita hao.

If I had known you were in the hospital, I would’ve visited you.

With Question Words

When used in a question, mohon acts as a marker requesting an opinion. Again, mohon suggests a preferred alternative, so when used with questions, we are asking what (or who, where, etc.) someone would do.

Manu mohon na manggaigi?

Where do you think they are?

Ngai’an mohon na ta fanali’i?

When do you think we all should meet?

Håyi mohon manggana gi ileksion?

Who do you think won in the election?

When used in conjunction with who, what, when, where, why and how questions, mohon usually follows the question word.

Other related expressions

Other expressions commonly used with mohon:

Ohala mohon…

In rapid speech ohala is often pronounced as “ola”. It is used to say that we wish something would happen.

Examples:

Ohala mohon uchan. I wish it would rain. Or If only it would rain.

August 29, 2018

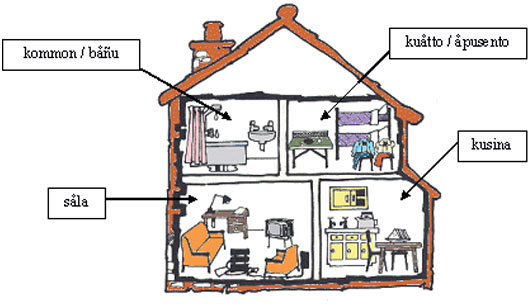

Chamorro Vocabulary for Things Around the House

Kuåtton i Gima’ Siha – Rooms of the House

apusento bedroom

såla living room

kusina kitchen

kommon bathroom; toilet (when one uses this word they are referring

to the room with the toilet)

båñu bathroom

kusinan sanhiyong outside kitchen

Kosas i Kuåtto – Things of the Room

gi apusento … in the bedroom

kama / katre bed

alunan pillow

såbanas blanket

aparadot dresser, closet for clothes

gi sala…

sofá sofa, couch

gi kusina … in the kitchen

kåhon ais refrigerator (lit. “ice box”)

foggon stove

hotno oven

labadot sink

grifu faucet

na’yan dishes

aparadot na’yan pantry, cupboard

gi kemmon … in the bathroom

påppet etgue / påppet kommon** toilet paper

espehos mirror

Otro Palabra – Other Words

luga wall

kisåme ceiling

åtof roof

bentåna window

satge floor

Betbo Siha – Verbs

maigo’ sleep

fakmåta wake up

fa’tinas to make, to cook

na’gåsgas to clean

båli to sweep

lampaso to mop

fa’gåsi to wash

arekla to fix, to arrange

Cultural Notes

The kusinan sanhiyong, or outside kitchen, is a common and significant feature of Chamorro homes. The kusinan sanhiyongis a necessary addition to all Chamorro homes for the reason that the traditional kitchen inside lacks the space required to prepare huge quantities of food. A typical Chamorro household will often be required to prepare food for a fiesta, a lisåyu*, or regular gupot** like birthdays or christenings. Preparing food in large quantities takes a significant amount of labor, and oftentimes this requires the help of many family members.

* a rosary

** a party

August 29, 2018

UM Verbs in Chamorro

UM verbs are a class of verbs that use the Yo’-type pronouns as the Subject pronouns – when the pronoun is the subject of the sentence. They are called UM verbs here because the affix um is used to conjugate these verbs. There are actually two affixes that are used to conjugate UM verbs, the first is UM and the second is MAN. Both will be explained here.

To conjugate with UM, there are two cases you must look for:

1) If the verb begins with a vowel simply prefix the verb with um and you have your first conjugation.

Example: o’mak -> umo’mak to bathe

2) If the verb begins with a consonant, you insert um into the first Consonant-Vowel pair in the first syllable.

Example: kati -> kumati to cry

The forms umo’mak and kumati are the “completed” forms of the verbs.

Umo’mak yo’. I bathed. / I showered.

Kumati yo’. I cried.

To conjugate the “continuous” form of the verb, the verb needs to undergo reduplication. Reduplication is when we repeat a syllable in a word.

1) With vowel-initial words, we simply need to reduplicate the vowel, but separating the duplicates with a glottal stop.

Example: o’mak -> umo’mak -> umo’o’mak

2) If the word begins with a consonant, we take the syllable that is the second to the last syllable in the word.

Example:

kånta -> kumånta -> kumakant. ; kanta (2 syllables) to sing

hugåndo -> humugåndo -> humugagando ; hugando (3 syllables) to play

NOTE: If the syllable contains more than just a consonant and vowel pair (like GAN in hugando), you need to duplicate only the first consonant-vowel pair.

The forms umo’o’mak, kumakanta, and humugagando are the “continuous” forms of the verbs.

Umo’o’mak yo’. I’m bathing.

Kumåkanta yo’. I’m singing.

Humugågando yo’. I’m playing.

Dual Case

When a plural pronouns is used with a verb conjugated with um the pronoun refers to only TWO people.

Examples:

Bumabaila ham. We are dancing. (Someone and I are dancing.)

Bumabaila hit. We are dancing. (You and I are dancing.)

Bumabaila hamyo. You two are dancing.

Bumabaila siha. They (2) are dancing.

Plural Case

To express the subject refers to three or more people, we use the plural prefix MAN.

Example:

Humånao siha. They went. (2)

Manhånao siha. They went. (3+)

When the prefix man is attached to words that start with a specific sound, certain changes can occur that may result in a completely new word. Look at the following examples.

| maN | Verb Initial | Result | Example |

| man | b | mb | man + baila -> mambaila |

| man | p | mp | man + peska -> mampeska |

| man | f | mam | man + faisen -> mamaisen |

| man | t | man | man + ta’yok -> mana’yok |

| man | s | mañ | man + såga -> mañåga |

| man | ch | mañ | man + chochu -> mañochu |

| man | k | mang | man + kåti -> mangåti |

| man | g | mangg | man + gimen -> manggimen |

List of UM Verbs

| kånta – sing baila – dance kåti – cry tånges – weep chålek – laugh chefla – whistle chochu – eat gimen – drink dåndan – to make music såga – to stay, to reside ekungok – to listen | o’mak – to bathe nangu – to swim kuentos – to talk peska – to fish pasehu – to cruise hugåndo – to play hånao – to go tohge – to stand essitan – to jest liliko’ – to go around ta’yok – to jump |

July 14, 2018

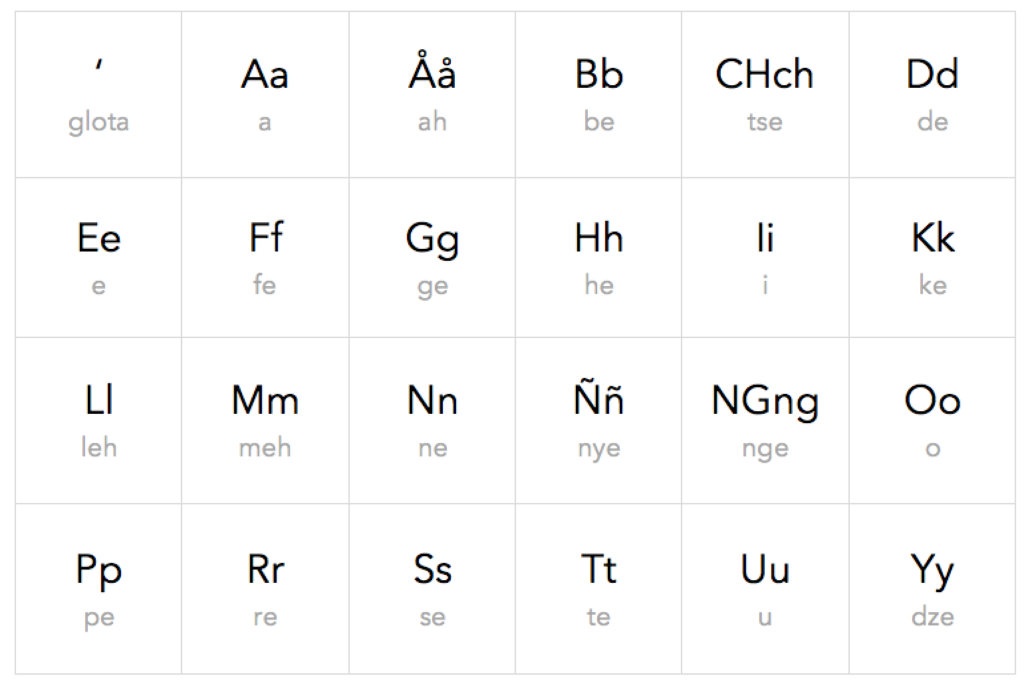

The Chamorro Alphabet

The Chamorro alphabet, or i atfabetu, is composed of 24 letters. The following table lists all the letters with their pronunciations.

NOTE: Those who grew up before the 1990s may have remembered the alphabet pronounced another way. This new way of pronouncing the alphabet was a shift away from the original pronunciations, which for some letters of the alphabet, was the exact same or close to the pronunciations of the Spanish alphabet. For example, the letters f, h, k, l and m, were pronounced eh-feh, ha-tsee, kah, eh-leh, and eh-meh, respectively.

The Vowels or I Buet

There are six vowels in the Chamorro alphabet.

a å e i o u

a – Pronounced like the a in tap or bat.

å – Pronounced like the a in father or papa.

e – Pronounced like the e in bed or test.

i – Pronounced like ee in feet.

o – Pronounced like the o in go, but shorter.

u – Pronounced like the oo in pool.

The Consonants or I Konsonante

There are eighteen consonants in the Chamorro alphabet including two semi-consonants: Ch, Ng .

ʹ b ch, d, f, g, h, k, l, m, n, ñ, ng, p, r, s, t, y

‘ – The glota, or glottal stop, can only be defined as a sudden stop. It’s that sound you hear when you say uh oh. The glota only follows a vowel and the addition not only changes the sound but the word’s meaning. Example: måta – eye, måta’ – raw, uncooked.

b – The letter b in Chamorro is slightly softer than its more aspirated English counterpart.

ch – The letter ch is described as a semi-consonant because it looks like two letters next to each other. However, the letter c in Chamorro does not exist. The letter ch in Chamorro is pronounced like the “ts” sound at the end of the word bats. So the word chålek, meaning to laugh, is pronounced tsah-lick, not tchah-lick.

d – The letter d is voiced, but it has no aspiration unlike the English d.

f – Pronounced like the English f

g – Pronounced like the English g.

h – Pronounced like the English h.

k – Pronounced like the English k, but much less aspirated.

l – Pronounced like the English l, but your tongue should be closer to the roof of your mouth (rather than the ridge).

m – Pronounced like the Eglish m.

n – Pronounced like the English n.

ñ – The letter ñ is pronounced like the ny in the English word “canyon.” The letter ñ was taken from the Spanish alphabet and easily adopted as many Chamorro words already had this sound (e.g. låña, meaning “oil”; danña’, meaning “to gather”).

ng – The letter ng is pronounced like the sound at the end of the word song. This may not seem so bad at first until you learn that there are Chamorro words that begin with ng. For example, the words nginge’, meaning “to smell,” and ngångas, meaning “to chew,” are pronounced NGEE-ngeeh and NGAH-ngass, respectively.

p – The letter p in Chamorro soft and not aspirated.

r – The letter r sounds like the Spanish trilled rr. At the beginning of words, the r may be pronounced like the English r, but trilled by other Chamorro speakers. To do this trilled sound, the back of your tongue will be widened so that it touches your molars and the tip of your tongue will be touching the ridge of your mouth as you exhale and attempt to vibrate the tip of your tongue. Or, you can just watch this How to Roll your R’s tutorial on YouTube.

s – Pronounced like the English s.

t – The Chamorro t is soft and not aspirated.

y – The letter y in Chamorro can also be considered a semi-consonant, because it is pronounced more like “dz” rather than a “yuh” sound in English.

Notes on Chamorro Letters

- With the exception of foreign words that have been Chamorrocized, most words in Chamorro generally do not end in the letters B, CH, D, G, H, L, Ñ, R, and Y.

- If a word sounds like it ends in a B, the word will be written as ending with a P. Same with the following letters: D as T, G as K. If you come across words that are written ending with these letters, then it is likely they were written with an older orthography. For example, the word for good maolek was often written as mauleg in older texts.

- Because a lot of Chamorro letters are softer than their English counterparts, there are some pairs of letters that may sound alike and may be interchanged by speakers. These sound pairs are the letters B and P, T and D, CH and Y, and G and K.

- The letters R and L are also often interchanged by native Chamorro speakers that you may hear different variations of the same word spoken. For example, the word arekla, meaning “to fix or put in order”, may sometimes be heard as alekla or even alegra.

- The letter glota is never at the start of a word and always follows a vowel.

July 7, 2018

“We” in Chamorro

The pronoun “we” in English can sometimes be ambiguous if the sentence is not constructed carefully. When it is used in conversation sometimes it is unclear if the person being spoken to is included in this mention of “we.” This ambiguity does not exist in Chamorro as there are two versions of “we”, defined as inclusive, meaning the addressee is included, and exclusive, the addressee is excluded.

The Inclusive/Exclusive “we” in Chamorro

Look at the sentence below and then look at the diagrams.

Speaker: Para ta fanhånao para i tasi! / We’re going to beach!

In Figure 1, the speaker is letting the other person know they’re included in the activity.

Speaker: Para bai in hanao para i tasi! / We’re going to the beach!

In Figure 2, the speaker is letting the other person know his plans.

A “We” for every situation

Once you’ve learned and are able to distinguish between the two “we”s in Chamorro, you can start learning the different words for them. The word for we changes depending on what you want to say.

Stative / Intransitive Sentence

A stative sentence is a basic sentence consisting of a subject and a predicate and is usually a descriptive sentence. For example, “We are happy” is a stative sentence. An intransitive sentence in Chamorro is one where there is no definite object involved. The Chamorro words for we here are inclusive hit and exclusive ham.

Chamorro ham.

We are Chamorro.

Chamorro hit.

We are Chamorro.

Chumocho ham.

We ate.

Mañocho hit gi resturan.

We ate at the restaurant.

Transitive Sentence with Definite Object

You may have noticed that the above sentence examples have the subject pronoun AFTER the verb. When a definite (specific) object is involved, the sentence structure changes to a structure familiar to English speakers: Subject Verb Object.

For example, in the sentence “He ate the apple”, the word “he” is the subject, “ate” is the verb, and “the apple” is the object. In Chamorro, the structure will be exactly the same. Except, here’s the catch, this only applies if the object is a definite object, that is, the object is specific. Our example works because the object “the apple” is specific; the apple refers to a specific apple located somewhere or bought by someone. If our example had been “He ate an apple,” then our sentence structure would revert back to Verb Subject, since there is no definite object involved.

The words for we in this sentence construction are inclusive ta and exclusive in.

In faisen si George.

We asked George.

Ta faisen si George.

We asked George.

Actor-focus Constructions

In English, the way someone emphasizes that the subject is responsible for an action is by adding the words “is the one who” or by putting stress on the subject when mentioning them verbally.

For example:

We ate the pizza. vs. We (were the ones who) ate the pizza OR We at the pizza.

To achieve the same thing in Chamorro, we use Actor-focus constructions and Emphatic pronouns. By themselves, the pronouns for the first-person plural are understood as US instead of WE, but are understood as WE in Actor-focus constructions. The emphatic we are the inclusive hita and exclusive hami.

Hami! Us! (Not you!)

Hita! Us! (Including you!)

Hami chumule’ i lamasa siha.

We (are the ones who) brought the tables.

Now that you’ve figured out there’s more to “WE” in Chamorro, you’re probably thinking you’re done, right? Well, not so fast. If you haven’t checked it out already, here’s how to say the singular and plural “you” in Chamorro.